Below find a quick-and-easy reference guide for major themes, historical events, and people you might need in order to orient yourself to the world of ZOOT SUIT, inside the plot and out.

TIMELINE OF EVENTS IN THE PLAY AND IN THE WORLD

From Kinan’s notes, this very useful pdf shows the progression of historical events and newspaper headlines related to the Sleepy Lagoon murder and its aftermath, WWII, the Riots, and the events of the play. ZOOT SUIT TIMELINES.

WHAT IS “CHICANO”

“Chicano/a/x” was originally a derisive term that Mexicans used to refer to other Mexicans, particularly poor ones, living in the United States. It is distinct from “Latino/a/x” which refers to anyone from Latin America, and “Hispanic,” as Cheech Marin writes:

Some ask “Why can’t you people just all be Hispanic?” Same reason that all white people can’t just be called English. Just because you speak English or Spanish does not mean that you are one group. Hispanic is a census term that some dildo in a government office made up to include all Spanish-speaking brown people. It is especially annoying to Chicanos because it is a catch-all term that includes the Spanish conqueror. By definition, it favors European cultural invasion, not indigenous roots. It also includes all Latino groups, which brings us together because Hispanic annoys all Latino groups. [read full article by Marin]

LUIS VALDEZ (1940- )

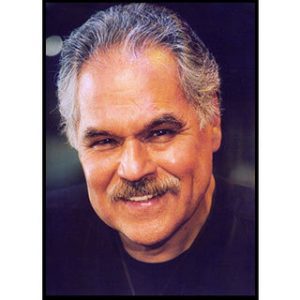

Actor, playwright, director of stage and screen, widely credited for being the “father of Chicano theatre.” Valdez was born in Delano, California – his parents were migrant farm workers, and as a child he moved around with them to work on the harvests around California. When his family settled down in San Jose, Valdez concentrated on theatre in school – he graduated from James Lick High School and San Jose State before working with the San Francisco Mime Troupe. In 1965, Valdez became part of the Chicano Rights Movement back in Delano, where Cesar Chavez (see below) was organizing the Delano Grape Strike (see below). For his part of this mission, Valdez created EL TEATRO CAMPESINO (see below). After this period, Valdez established Chicano cultural centers in Del Ray and Fresno before moving his company to San Juan Bautista. He was a founding member of the Cal State Monterey Bay Teledramatic Arts and Technology Department, and was awarded the Presidential Medal of Arts by Barack Obama in 2015.

Actor, playwright, director of stage and screen, widely credited for being the “father of Chicano theatre.” Valdez was born in Delano, California – his parents were migrant farm workers, and as a child he moved around with them to work on the harvests around California. When his family settled down in San Jose, Valdez concentrated on theatre in school – he graduated from James Lick High School and San Jose State before working with the San Francisco Mime Troupe. In 1965, Valdez became part of the Chicano Rights Movement back in Delano, where Cesar Chavez (see below) was organizing the Delano Grape Strike (see below). For his part of this mission, Valdez created EL TEATRO CAMPESINO (see below). After this period, Valdez established Chicano cultural centers in Del Ray and Fresno before moving his company to San Juan Bautista. He was a founding member of the Cal State Monterey Bay Teledramatic Arts and Technology Department, and was awarded the Presidential Medal of Arts by Barack Obama in 2015.

THE LIVING NEWSPAPER

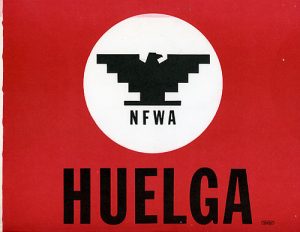

The “Living Newspaper” is a theatrical tradition at least as old as classical Greece, when actors would travel with the armies through major wars and write newsworthy plays for audiences back home. In the early years of the 20th century, politically activist theatre troupes (mainly but not exclusively Marxists) began using newspaper stories as base material for the creation of dramas that tell the human stories behind them. An antidote to mainstream melodrama, musical theatre, and social realism, the Living Newspapers were quick and easy to produce and became a popular tool for organizing communities and getting information out fast. In Russia, the new Communist regime fostered the “Blue Blouse” theatre troupes that would perform in factories and on farms. Hallie Flanagan, the charismatic director of the Federal Theatre Project, wrote her own ripped-from-the-headlines play, It Can’t Happen Here, and then supported the development of Living Newspapers in the FTP, including celebrated works like Triple-A Plowed Under, Power, and Spirochete. Luis Valdez drew from this tradition to create his actos in support of the Huelga movement (see below) to perform for groups of migrant workers on the farms and in the picket lines from the backs of flatbed trucks. Zoot Suit leans heavily on this tradition, emphasizing it with the opening scene during which the Pachuco enters after slitting a hole in a gigantic newspaper – in fact, the Press is a character in Zoot Suit that attempts to counterbalance and outmaneuver the Pachuco in their psychomachia over the soul of Henry Reyna and, by extension, the United States.

CÉSAR CHÁVEZ (1927-1993)

Chávez was an American civil rights leader born in Yuma, AZ, to a Mexican-American landowning family that was cheated out of everything during the Great Depression and moved to California to become migrant farm workers. To prevent his mother from having to do field work, Chávez dropped out of school in seventh grade to work in her place. In 1946, Chávez joined the Navy, a period he would later refer to as “the worst two years of my life.” In the 50’s Chávez became a community organizer for farm workers and in 1962 co-founded the National Farm Workers Association (later to become the United Farm Workers, or UFW) with Dolores Huerta (see below). In the 1970’s, Chávez and Huerta fought hard for advances in civil rights for farm workers, who were overwhelmingly Mexican-American, as well as wage equity and improved working conditions, largely by organizing strikes and other labor actions. Chávez also worked hard to prevent illegal immigration, feeling that it undermined US workers and encouraged exploitation of the undocumented. He died while working in Arizona, but was not given military honors until 2015. His birthday is celebrated as a state holiday in California, Texas, and Colorado.

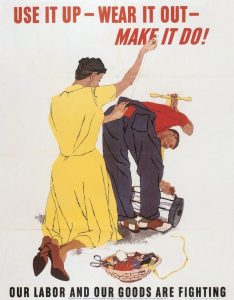

WORLD WAR II and CHICANOS

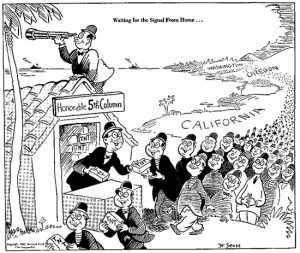

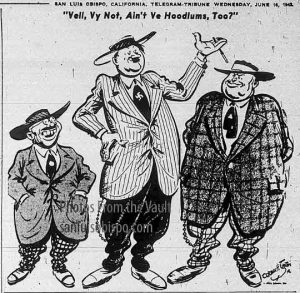

A surprising cartoon from Dr. Seuss, who was an editorial cartoonist during WWII before becoming a beloved children’s book author.

When the US entered the war in 1942, the children of Mexican immigrants outnumbered Mexican immigrants living in the US – more than a million individuals. Even as Chávez and others like Luisa Moreno were organizing Chicano laborers (Moreno organized cannery and packing workers in San Diego) young Mexican-Americans came to see participation in the war effort as a means of combatting racism, gaining professional skills that would pull them from poverty, and asserting their own identities as Americans. This, perhaps not unexpectedly, backfired. Southern California became a particularly important region for military manufacturing, and suspicion that the Japanese-Americans living in California might be fifth-columnists and saboteurs led to their confinement in internment camps (Valdez’ most recent play, Valley of the Heart, dramatizes relationships between Japanese landowners and Chicano workers during this tragic period). With the Japanese in camps, public racism turned against Chicanos. Unable to hold jobs that would protect them, were drafted in huge numbers. Mexican-American women picked up the slack in factories, fields, and in the home. Probably about 500,000 Mexican American men joined the armed forces, and earned more Congressional Medals of Honor than any other ethnic group.

THE DELANO GRAPE STRIKE

On September 8, 1965, a strike by the United Farm Workers against the California grape-producing industry began – it would last five years. The strike began when the representatives of the mostly Filipino and Mexican-American farm laborers, among the lowest-paid workers in the US at the time, walked off farms in Delano, California, to demand that their wages be increased to meet the federal minimum wage. Thousands of workers followed suit, and César Chávez (above) was a key figure in uniting the various labor groups, making the plight of farm workers a national cause, and gaining a charter for the UFW from the AFL-CIO. Chávez also convinced longshoremen at the Oakland docks not to load grapes into ships – ten thousand tons of grapes were spoiled as a result. The strike eventually involved more than 10,000 workers in cities as far flung as Boston, Pittsburgh, and Detroit. The strikers’ battle cry was “¡Huelga!” (Strike!). Note that the colors of the strike flag are red and black, like those of the Pachuco – these are also the mythic colors of the Aztec god Tezcatlipoca.

On September 8, 1965, a strike by the United Farm Workers against the California grape-producing industry began – it would last five years. The strike began when the representatives of the mostly Filipino and Mexican-American farm laborers, among the lowest-paid workers in the US at the time, walked off farms in Delano, California, to demand that their wages be increased to meet the federal minimum wage. Thousands of workers followed suit, and César Chávez (above) was a key figure in uniting the various labor groups, making the plight of farm workers a national cause, and gaining a charter for the UFW from the AFL-CIO. Chávez also convinced longshoremen at the Oakland docks not to load grapes into ships – ten thousand tons of grapes were spoiled as a result. The strike eventually involved more than 10,000 workers in cities as far flung as Boston, Pittsburgh, and Detroit. The strikers’ battle cry was “¡Huelga!” (Strike!). Note that the colors of the strike flag are red and black, like those of the Pachuco – these are also the mythic colors of the Aztec god Tezcatlipoca.

The corporations who suffered for this retaliated in a variety of ways, including intimidation and thuggery. Demonstrators were put in hospitals by hired strikebreakers, and union meetings were violently disrupted. Thanks to a supportive consumer boycott, endorsement from unions and religious groups, community organizing, and non-violent resistance, in 1970 under Chávez’ leadership the UFW was able to establish a collective bargaining agreement with the corporations.

LALO GUERRERO (1916-2005)

Born in Tuscon, Arizona, Guerrero was the son of a railroad worker. From his youth he pursued a dream of performing and writing music. In the 1940’s Guerrero was in Hollywood performing in night clubs and movies, and bought his own nightclub in the 1960’s, “Lalo’s” that was the place to see and be seen in LA for many years. Over his career he recorded more than 700 songs, including many about the plight of migrant farm workers and about Cesar Chavez himself. Beloved by millions of Americans and others from all over the world, Guerrero is considered the “Father of Chicano Music,” and was honored with the National Medal of Arts by Bill Clinton in 1991. Guerrero’s music as as intrinsic to the Pachuco style as the Zoot Suit itself. Here’s a sample: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M4_oD56Pzg8

IGNACIÓ GOMEZ

Born and raised in East LA the son of Mexican immigrants, Gomez was drafted into the US Army in 1966. He painted four murals at Fort Ord (about an hour south of Santa Cruz) when he was stationed there. He became a successful commercial artist in the 1970’s, illustrating a Beatles album in 1976. He is now a world-renowned, highly recognized artist and professor. He writes:

I live i

n two worlds, creating art to support a family and creating art to support my community, the Latino community. In one of my worlds, I illustrate Stephen Spielberg, John Paul Jones, and Steve Jobs; in the other I paint Edward James Olmos, Congressional Medal of Honor Recipient Eugene Obregón, and César Chávez. One of these two worlds puts food on the table, while the other offers nourishment that bread could not fulfill. This hunger is satisfied with powerful images of Latinos on a quest for higher education, becoming professionals, and accomplishing great things. This is where my satisfaction arises as a Chicano artist.

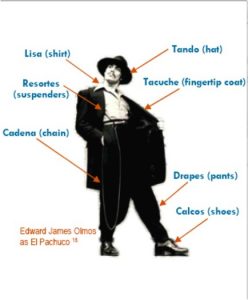

ZOOT SUITS

“Zoot” means “worn or performed in an exaggerated style. The name “zoot suit” is a riff on rhyming slang popular all over America in the 30’s and 40’s. After the bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941, the US Office of Price Admini stration grew concerned that the material needs of the war effort might produce shortages in commodities like gasoline, metal, electricity, sugar, meat, butter, nylon, silk, batteries, and rubber just to name a few items. Dog food, for example, could not be sold in tin cans, and so dry varieties were invented. A slang pickup line at this time was “hey, sugar – are you rationed?” Fabric was also rationed – before the war, a standard men’s suit came with a vest and two pairs of pants. The “Victory Suit,” however, was single-breasted, with narrow lapels, no cuffs, no pocket flaps, no vest, and only one pair of pants. The Zoot Suit, on the contrary, consisted of a extremely long jacket (a finger-tip or “Tacuche” jacket), very wide lapels, padded shoulders, with high-waisted, full-cut baggy trousers that tapered to narrow cuffs, held up with wide suspenders, an elaborate vest, worn with wide-lapelled shirts and often a very wide-brimmed hat. A status symbol among ethnic minorities including Mexican-, Black- and Phillipino-Americans, wearing a the Zoot Suit was an act of defiance during wartime, and Zoot Suits could only be acquired through bootleg tailors (See Zoot Suit Riots below).

stration grew concerned that the material needs of the war effort might produce shortages in commodities like gasoline, metal, electricity, sugar, meat, butter, nylon, silk, batteries, and rubber just to name a few items. Dog food, for example, could not be sold in tin cans, and so dry varieties were invented. A slang pickup line at this time was “hey, sugar – are you rationed?” Fabric was also rationed – before the war, a standard men’s suit came with a vest and two pairs of pants. The “Victory Suit,” however, was single-breasted, with narrow lapels, no cuffs, no pocket flaps, no vest, and only one pair of pants. The Zoot Suit, on the contrary, consisted of a extremely long jacket (a finger-tip or “Tacuche” jacket), very wide lapels, padded shoulders, with high-waisted, full-cut baggy trousers that tapered to narrow cuffs, held up with wide suspenders, an elaborate vest, worn with wide-lapelled shirts and often a very wide-brimmed hat. A status symbol among ethnic minorities including Mexican-, Black- and Phillipino-Americans, wearing a the Zoot Suit was an act of defiance during wartime, and Zoot Suits could only be acquired through bootleg tailors (See Zoot Suit Riots below).

The proper stance for someone wearing a Zoot Suit is to lean jauntily backwards in an exaggerated slouch, further expressing a certain joyful disdain.

See the full cartoon of ZOOT SUIT CAT (1944)

PACHUCO/A

Pachuco refers to a particular subset of Chicano culture present in Los Angeles in the 1930’s and 40’s. Pachucos originated in El Paso, Texas (also known as “Chuco Town”), and Ciudad Juaréz, Mexico and became railroad workers, following the trains north and west.

[Why exactly El Paso is called “El Chuco” or “Chuco Town” is much debated. “Chuco” means “disgusting” or “filthy” in Spanish, but whether this refers to El Paso or the people who live there I cannot determine.] -MC

The celebrated Mexican author Octavio Paz wrote about Pachucos:

“What distinguishes them, I think, is their furtive, restless air: they act like persons who are wearing disguises, who are afraid of a stranger’s look because it could strip them and leave them stark naked…. This spiritual condition or lack of a spirit, has given birth to a type known as the pachuco. The pachucos are youths, for the most part of Mexican origin, who form gangs in southern cities; they can be identified by their language and behaviour as well as by the clothing they affect. They are instinctive rebels, and North American racism has vented its wrath on them more than once. But the pachucos do not attempt to vindicate their race or the nationality of their forebears. Their attitude reveals an obstinate, almost fanatical will-to-be, but this will affirms nothing specific except their determination . . . not to be like those around them.”

-The Labyrinth of Solitude (1967) pp 5-6

Pachuca culture was another phenomenon of the moment – women would also dress flamboyantly in variants of the male style, wearing the zoot suit or pieces of it tailored to fit the female body, complete with pocket chains and platform shoes, or fishnet stockings, elaborate dresses, and bobby socks. Pachucas who dressed in this style were challenging traditional gender roles in American culture as well as in Latinx culture – “good girls” simply did not dress this way – and Pachucas were often lumped into to prejudices about the violent, gangster lifestyle attributed to male Zoot-Suiters.

CALÓ

Caló, or “pachuquismo,” is a highly specialized slang spoken by Pachucos. Its origins come from many places, including the dialect spoken by Spanish gypsies (zincaló). It is not “Spanglish” (Anglicized Spanish) nor it is Hispanicized English, although it takes elements from both, and also includes Nahuatl (a language spoken by indigenous peoples of Central America). It is elegantly poetic, rife with rhyming, alliteration, neologisms, jokes and puns. For more, see the GLOSSARY.

THE SLEEPY LAGOON MURDER TRIAL

Enrique “Henry” Reyes Leyvas (1923-1971)

Henry, known to his friends as Hank, was one of the many victims of police misconduct and brutality in Los Angeles, merely because of his Mexican roots, such as many were targeted by their ethnic backgrounds during the 1940s. He was constantly arrested under false pretenses along with his friends, such as when he and his brother were charged with automobile theft by the police who refused to believe that it was their father’s car. Unfortunately, his life complicated itself, beyond merely day to day racism, he became entangled in the Sleepy Lagoon murder trials. On August 1, 1942, Henry, and youths from 38th Street, were enjoying the Sleepy Lagoon as a social spot, when suddenly he and his girlfriend, Dora, were harassed and beaten by a group of boys from Downey. The conflict incited Henry to seek aid from his friends at 38th Street yet when they returned, the group was gone. Amid the chaos, they came across a party held by the Delgadillo Family, discovering that the Downey boys had been banned from the party for causing trouble, on edge from the previous attacks, the tensions rose and there was a scuffle, it was short but the next morning it would prove to not be so insignificant. The following morning the body of partygoer José Díaz was found in critical condition, with blunt head trauma, and soon was pronounced dead. On August 2nd, the LAPD apprehended 600 African American and Mexican American individuals on suspicion of involvement with the death, using the ‘Mexican Problem’ and constant outbreaks of juvenile delinquency as a basis for the raids. The police took advantage of Henry’s record, to keep him detained along with twenty-two others as responsible for what was determined as the murder of José Díaz.

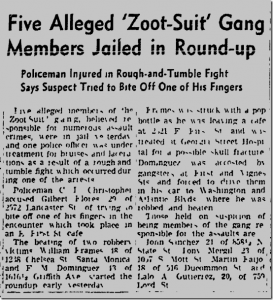

During the lengthy trial of People v. Zamora (beginning in October 1942 and ending in January of 1943) racial prejudice was greatly illustrated by such claims as that of the mens’ sense of style, their Zoot Suits, being considered evidence towards their guilt in the crime. A claim which triggered increased outcry from the public since many other ethnic minorities were known for wearing Zoot Suits, as well as the unlawful methods utilized in court to convict without evidence. Seventeen of the twenty-two were convicted, Henry and two others charged with first degree murder, sent to the San Quentin Prison and eventually to Folsom Prison. The trial caused ‘Zoot Suit’ riots in Los Angeles as well as nationally (mentioned below).

In 1944, the Sleepy Lagoon Defense Committee, in collaboration with columnist Matt Weinstock of The Los Angeles Daily News, managed to transpire the cause of the unjust conviction of the Mexican youth in the Sleepy Lagoon case and gain support from ethnic groups, Hollywood celebrities, and others nationally. Although the issue of comprehending the Pachuco culture, that was being targeted in Los Angeles and across the nation, remained mysterious and misinterpreted by both advocating and undermining sides. The SLDC finally gathered enough funds through their outreach to get a court appeal for the 38th Street boys. In October, Judge Clement Nye overturned the original verdicts citing a mistrial due to bias in the judiciary and lack of evidence from the prosecutor, in addition to a violation to the sixth amendment of the United States Constitution; granting Henry and the remaining convicted men their release.

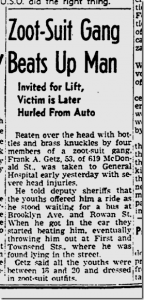

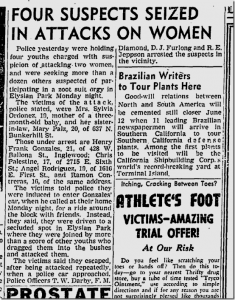

THE ZOOT SUIT RIOTS

Often, the riots are associated with the Sleepy Lagoon murder trials (above) where Mexican-Americans were singled out and associated with gangsterism and criminality by Los Angeles authorities. However, what sparked the major outbursts of riots was an incident on May 30th, 1943 where about a dozen sailors and soldiers claimed they were attacked by zoot suiters. This officially made the “zoot suit” a symbols of anti-patriotism – a very serious charge during wartime.

For five nights straight, large cohorts of white servicemen in their suits left their stations in Los Angeles to pick out zoot-suiters, beat them up, and strip them of their suits. Each night, police officers stood by waiting, and when caught, the white soldiers claimed to be “vigilantes” while the real victims, the zoot suiters, were unfairly arrested instead. Eventually, U.S servicemen started assaulting Blacks and Filipinos, no matter where they were (randomly in cafes and theaters) whether they wore zoot suits or not. The number of attacks dwindled, and the rioting had largely ended by June 10. In the following weeks, however, similar disturbances occurred in major cities all over the US. Finally on June 8th, the U.S military finally barred servicemen from leavi ng their barracks and LA City Council passed a resolution to ban the zoot suit attire.

ng their barracks and LA City Council passed a resolution to ban the zoot suit attire.

As the riots died down, California Gov. Earl Warren ordered the creation of a citizens’ committee to investigate and determine the cause of the Zoot Suit Riots. Following the riots, there was no justice was made for the ethnic minorities that were wrongfully convicted. Many political figures became defensive and feared the riots negative media towards their city’s reputation. F or example, both the Los Angeles Mayor and the President of the California State Chamber of Commerce denied racial prejudice as the main cause for the riots even after the first Lady Eleanor Roosevelt statement that it was the fear Mexican-Americans in southwest. Similarly, the media dismissed race as the issue, and claimed that juvenile delinquents were the cause of such chaos. Local papers, like the L.A Times, framed the racial attacks as a “vigilante response” to an immigrant crime wave. In America, the incident triggered similar attacks against zoot suit-wearing ethnic minorities (African Americans, Latinos, Filipinos, Jewish, etc) in Chicago, San Diego, Detroit, Philadelphia and New York. These riots would create a strong set of civil rights leaders, including a young zooter pimp known as Detroit Red whose experience when the fighting spread to New York was pivotal in his transformation into Malcolm X.

or example, both the Los Angeles Mayor and the President of the California State Chamber of Commerce denied racial prejudice as the main cause for the riots even after the first Lady Eleanor Roosevelt statement that it was the fear Mexican-Americans in southwest. Similarly, the media dismissed race as the issue, and claimed that juvenile delinquents were the cause of such chaos. Local papers, like the L.A Times, framed the racial attacks as a “vigilante response” to an immigrant crime wave. In America, the incident triggered similar attacks against zoot suit-wearing ethnic minorities (African Americans, Latinos, Filipinos, Jewish, etc) in Chicago, San Diego, Detroit, Philadelphia and New York. These riots would create a strong set of civil rights leaders, including a young zooter pimp known as Detroit Red whose experience when the fighting spread to New York was pivotal in his transformation into Malcolm X.

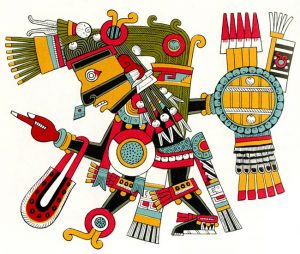

Aztec Mythology

The Aztecs sustained a highly complex theology, which embraces the concept of multiplicity. Firstly, the Aztec story of the creation of the world chronicles the creation and destruction of multiple universes in a chronology which does not definitively acknowledge any particular universe as the true or even contemporary one. Instead there is a suggestion of multiple versions of events, with no hierarchy of correctness between them, and no mutually exclusive boundary. The concept, in essence, is that the cosmos is vast enough to embody multiple, perhaps conflicting, truths at the same time. This ideology is of particular interest to this production considering the multiple and conflicting but simultaneous endings of Henry Reyna’s story.

A second way in which Aztec Mythology highlights multiplicity is in its appreciation of the opposing forces of order and chaos. An important thing to note when examining this binary in the context of Aztec culture is that neither one of these concepts is considered objectively good or evil. The god Quetzalcoatl is associated with harmony, order, and daylight. Meanwhile his brother and counterpart Tezcatlipoca is a trickster god of conflict, chaos and is often associated with night, which to the Aztecs was a time where the boundary between the natural and the supernatural blurred, inviting dynamic spiritual change. Tezcatlipoca and his reflections in modern media, of which El Pachuco is a prime example, are often lampooned by white western audiences for two reasons. One of course is either conscious or unconscious racist rejections of indigenous theological concepts. Two, because any figure which suggests the image of Tezcatlipoca is going to, by its nature, upset the status quo. Christianity tends to demonize divine trickster figures, and the Catholic church has put a monumental amount of historical and contemporary effort into linking the images of more cthonic divine figures to its own images of Satan. But in Aztec cosmology, Tezcatlipoca is no more or less good or evil than his brother, Quetzalcoatl. Nor are the concepts he embodies any more or less important to cultural discourse or spiritual wellness.